Alice Stockton-Rossini - Shipbottom, NJ

Do you have to experience it to believe it? Believe it. This is not the flu.

Christina Castellanos - Bound Brook, NJ

Suffered so badly that she was afraid to go to sleep for fear she wouldn’t wake up.

Shawn Bennett - Mountain Lakes, NJ

It was the least I could do to hopefully give someone a chance to beat the disease.

Patti Merseles - Williamstown, NJ

My breathing was getting worse and worse and worse and I was scared.

By Volunteer David Murphy

It wasn’t just something they wanted to do, it was something they felt they had to do.

Giving blood is a simple act, but a poignant one. It connects individuals in a way that science can only partially account for. In giving blood, you are offering part of your body to another, in the hopes that your good health can be shared. Rarely has there been a time of greater need, or more of a demand for blood and its healing properties.

People who have contracted COVID-19, who have experienced what the Novel Coronavirus can do to your mental and physical health, know how precious those healing properties can be. “If you get it, and you are lucky enough to recover, you have to give blood,” says Alice Stockton-Rossini, a coronavirus survivor from Ship Bottom, New Jersey. More than 120,000 Americans have fallen victim to the virus, also known as COVID-19, while more than 2.3 million have tested positive for the disease. “Knowing the fear of this virus and knowing what it does to you, if I can help these people, I’m going to do it by any means necessary,” says Christina Castellanos, a Bound Brook resident who suffered so badly that she was afraid to go to sleep for fear she wouldn’t wake up. For those who have gone through the mental and physical anguish of the disease and come out the other side, there is an overwhelming sense of gratitude for having dodged a bullet, and a sense of determination to do whatever they can to help others do the same.

The Rossini’s fell ill shortly after Alice threw a party for her mother in early March, just days after the very first American patients were identified in New York. “The next day,” she says, “my mom got sick and my dad got sick. Several members of the church (where the party was held) ultimately died.” A close family friend and next-door neighbor also fell victim to the disease. “When we got tested for antibodies and we realized we could give plasma, it’s the only thing you have,” says Alice. “It’s the only thing you can do.”

Patti Merseles, a nurse from Williamstown, thought her allergies were acting up, until she found herself struggling to breathe. “My breathing was getting worse and worse and worse and I was scared,” she says. When she finally called the doctor, “the nurse was horrified. She could hear how bad it was over the phone. She says you need to call 911 and go to the hospital.” Even after recovering, Patti suffers from exhaustion and worries that the virus may have done permanent vascular or neurological damage.

For Christina Castellanos, the experience of coming down with coronavirus “felt like I was being stabbed all over my body from the inside.” She lost her sense of taste and smell and still worries about long-term damage. Even among those who didn’t experience that extreme level of suffering, the desire to donate is strong.

As a health care worker, Lindsey Ball had already seen plenty of patients by the time she tested positive. “Since I’m on the frontlines,” she says, “I feel like I’ve seen how patients are struggling right now… a lot of people are getting hit a lot harder with the virus than I did.”

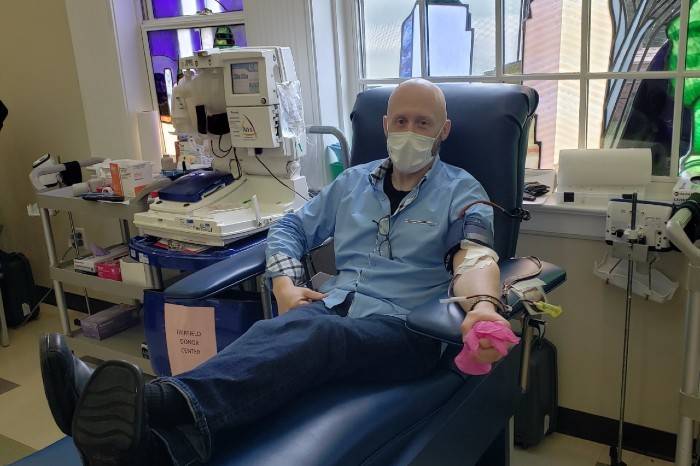

The use of convalescent blood plasma began about a hundred years ago and was used widely to treat scarlet fever and the Spanish flu. Doctors began taking blood plasma from people who had recovered from infection in order to poach the antibodies their bodies had produced. Then, the plasma and antibodies were injected into others in order to boost their own defense systems. In other words, the antibodies act as a form of borrowed immunity that can mean the difference between life and death, particularly for critically ill patients. Plasma is donated using an apheresis process, meaning blood is drawn from one arm, sent through a high-tech machine that strips out plasma, then safely returns blood cells and platelets to the donor.

The American Red Cross, the FDA and industry partners have teamed up in a unique effort to support the collection and distribution of convalescent plasma. It is the largest program of its kind ever attempted by the Red Cross in its nearly 140-year history.

“I heard about (the program) on the news before I got sick,” says Liz Mason, of Sicklerville. “Once I found out I had COVID, I went on Google and found the Red Cross. I just wanted to help out in any way I could. I had autoimmune issues for over 15 years and a lot of times I couldn’t give blood. This was a way I could help and it’s something I wanted to do.”

When asked about the decision to donate their plasma, the response from donors was universal: it wasn’t just something they wanted to do, it was something they felt they had to do. Castellanos says, “God gave me a second chance, so that was my way of giving back to the man above.” While donating, Stockton-Rossini remembered her friend and brother-in-law who died from the virus. “I don’t like needles, and all I could think of was, ‘Think about who you are doing it for. You’re doing it for Sergio. You’re doing it for Sandy - and anyone else down the road who may be saved.’”

Mountain Lakes Police Chief Shawn Bennett has a unique take, based on his line of work. “A police officer does the job so that they can help people whenever possible. COVID-19 made people around the world feel powerless. Law enforcement was not spared that feeling.” Chief Bennett did his part by enforcing mitigation efforts before testing positive in late March, albeit with minor symptoms. “As soon as I heard about the Red Cross convalescent plasma program, I applied to donate. I felt it was my duty to do so and the least I could do to hopefully give someone a chance to beat the disease. I had too many friends that lost loved ones. I couldn’t just do nothing.”

The Red Cross began testing qualified donors two months ago, building the program with unprecedented speed. Dr. David Moolten, medical director for the Red Cross Penn Jersey Blood Services Region, says he saw an enormous amount of passion on behalf of doctors and donors. “I’ve been doing this a long time,” he insists. “And I’ve never seen anything like it – not even close.” Moolten says right now, the Red Cross is “caught up and we’re pretty confident we won’t run into a shortage. There’s been so many people that have gotten this that we’ve been able to collect a lot and get ahead of this. We’re feeling pretty confident about the stockpile in case of more surges.” However, he says “no one should be feeling complacent – we have a long way to go.”

At the moment, New Jersey is seeing its number of coronavirus cases trending down. However, hundreds of cases and dozens of deaths are still being reported every day. Initially, the demand was high and the supply was low. According to Dr. Moolten, the Red Cross is able to meet the immediate demands from patients, but he says there’s another reason to give: it helps scientists trying to find even more effective treatments. “The donations are being used as a jumping off point for efforts to make antibody treatments like hyperimmune globulin, which can be delivered as a shot,” he says. “Or it can be used as part of efforts to develop an even more specific therapy, creating antibodies that could be made artificially to directly attack COVID-19.”

In order to donate, you must be at least 17 years old and 110 pounds. Donors must have a prior verified diagnosis of coronavirus but be fully recovered, symptom-free and in good health Donors of all types are needed, but those with the blood type AB are most sought after since their blood can go to anyone.

With concerns about a possible second wave this fall, the Red Cross is encouraging people to keep donating in order to maintain a sufficient supply that can be readily available for hospitals going forward. For those that believe the pandemic is no longer anything to worry about, these COVID survivors have a message: it is. Alice Stockton-Rossini put it bluntly. “Do you have to experience it to believe it? We're here to say - believe it. This is not the flu. There’s every reason to believe this is real. And once you believe it’s real, you have to give the antibodies.”

If you have recovered from COVID-19 and are interested in donating convalescent plasma, the Red Cross will continue to need donors in the weeks and months ahead and encourages fully recovered individuals to complete the Donor Information Form on RedCrossBlood.org/plasma4covid. Once you register, someone from the Red Cross will follow up in three to five days. Individuals who qualify to donate convalescent plasma will be given an appointment and location at that time.

The American Red Cross New Jersey Region is extremely grateful to, and proud of, the donors from our area who have joined the movement to give COVID-19 convalescent plasma, providing hope for patients and their families during this coronavirus pandemic. Your willingness to step forward and donate antibody rich plasma in order to help the Red Cross meet the immediate emergency need for COVID-19 convalescent plasma for critically-ill patients is greatly appreciated by all.