By Susan Gallagher

His upbringing could have consigned Jamie Grayson to a life of dead-end jobs and endless struggle.

“I was one of five children of a single mom, who left school in the 10th grade. We were on welfare, but my mom offered us strong guidance and great love. As a long-time school cafeteria worker, she welcomed kids from all backgrounds into our home offering a safe place full of love. With help from my grandmother, she managed to raise four boys who finished college on athletic scholarships, built successful careers and contributed to their communities,” he said.

For decades, Jamie Grayson has been actively involved in local schools, businesses, religious organizations and as a senior-level executive in the financial services industry---managing bank branches, overseeing commercial business portfolios and connecting entrepreneurs with the financial vehicles they need.

He and his siblings succeeded as African-Americans in a predominantly white town of 2,500 (Plattsburg, MO), where many foundational building blocks of treating others with respect were established.

They also lived in a small apartment where their only sister was suffering from full-blown sickle cell disease. Tonya died at age 16. Jamie’s older brother Rodney did not carry the trait, but saw firsthand the impact of sickle cell through his siblings. Jamie, his twin brother Jason, and his younger brother Marcus all carry the sickle cell trait, as does Jamie’s son, Jaxson, age 15.

Those, like Tonya, with sickle cell disease have red blood cells that are crescent- (or sickle-) shaped. This abnormal shape makes it difficult for the cells to travel through the blood vessels. As the sickle cells clog the blood vessel, they can block blood flow to various parts of the body, causing painful episodes and raising the risk of infection. In addition, sickle cells die earlier than healthy cells, causing a constant shortage of red blood cells---also known as anemia. The condition also requires blood transfusions.

In contrast, Tonya’s brothers with the sickle cell trait have inherited one sickle cell gene and one normal gene. They have both normal red blood cells and some sickle-shaped red blood cells. Most people with sickle cell trait do not have any symptoms of sickle cell disease.

Jamie has always found value in educating others about various things, but sickle cell is a subject that is near and dear to his heart. A decade ago when he earned his master’s degree in education from William Woods University, he based his capstone paper on educating coaches about the special needs of athletes with sickle cell.

“September is Sickle Cell Awareness Month—so it’s appropriate that we remind everyone and especially those in the black community that donating blood is vital,” he said.

That’s especially true now, when due to COVID-19, blood drives are being cancelled in multiple locations, and the number of African-American donors has dropped from 15,000 in 2019 to 2,700 thus far this year.

“It is also important to tell everyone that those with the sickle cell trait CAN give blood,” said Jamie. “Our community needs to realize we play a significant role in helping those suffering from this disease.”

Suffering is not new to Jamie, who was only nine years old when his sister died. He watched her cry in pain all the years he knew her. “I especially recall from those years a story of a teacher who was angry at my sister because Tonya was crying in class, and the teacher did not realize that she was experiencing pain from having sickle cell.”

His sister’s early death, the loss of a sister-in-law at age 34 and his mother three years ago at age 64 made Jamie realize the importance of making the most of the time he has. “Time is the greatest equalizer—we all have only 24 hours of each day to define what we want to do and to make a difference. Our stories will be told when we depart, and each of us must determine what that story will be.”

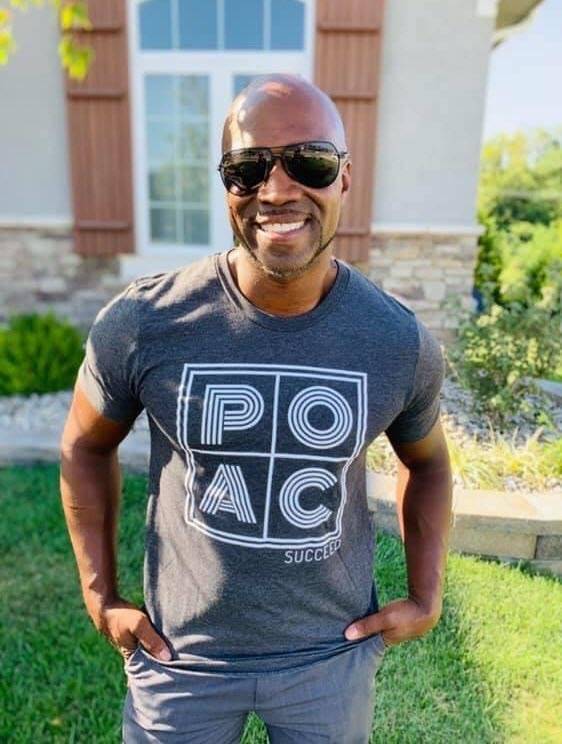

Jamie believes his story will be about the nonprofit he founded to counter the growing epidemic of bullying in schools and the workplace. In operation only a year, People Of All Colors Succeed (POAC Succeed) now has over 1,000 ambassadors working throughout schools and communities to empower individuals to be ambassadors for change.

Through his program, each ambassador goes through a three-week program, where emotional intelligence is the focus during group discussion and activities. They reach out to teens who are depressed – even suicidal -- and to others who are victims of cyber bullying or abusive language.

“Our ambassadors learn how the intent and impact of words affect every interaction we have,” he said. “With every touch-point, every day, we will close the gap between societal injustices and equality. Whether it's age, race, gender, religion, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status or otherwise. If we can eliminate the differences we perceive as barriers, we can then embrace the many similarities we may have never known existed.”

POAC Succeed operates primarily in Kansas City, but has ambassadors in 30 of the 50 states, and had reached outside the United States to places like Ghana, Barcelona, Scotland and several others.

Jamie likens the organization to the center of a spider web with plans to extend its reach out to other cities to share what its ambassadors are doing to connect with people in Kansas City and around the world.

His strong belief is that “through acceptance of others and encouraging courageous conversations, change will come.”

More African American blood donors are urged to make a blood donation appointment by downloading the Red Cross Blood Donor App, visiting RedCrossBlood.org, calling 1-800-RED CROSS (1-800-733-2767) or enabling the Blood Donor Skill on any Alexa Echo device.

How donations from African American blood donors help sickle cell patients

About 100,000 people in the U.S., most of whom are of African or Latino descent, are living with sickle cell disease, making it the most common genetic blood disease in the country.

Blood transfusion helps sickle cell disease patients by increasing the number of normal red blood cells in the body, helping to deliver oxygen and unblock blood vessels. Patients with sickle cell disease depend on blood that must be matched very closely – beyond the A, B, O and AB blood types – to reduce the risk of complications. Some of these rare blood types are unique to specific racial and ethnic groups, and because of this, sickle cell disease patients are more likely to find a compatible blood match from a blood donor who is African American.