Philadelphia is home to many national firsts. The Library Company of Philadelphia, founded by Benjamin Franklin in 1731, was the nation’s first library. In 1740, the University of Pennsylvania became the first university in the U.S. and has the distinction of opening the nation’s first medical school (1765) and the world’s first college-level business school, Wharton (1881). And the Philadelphia Zoo, home to over 13,000 animals, was the nation’s first zoo.

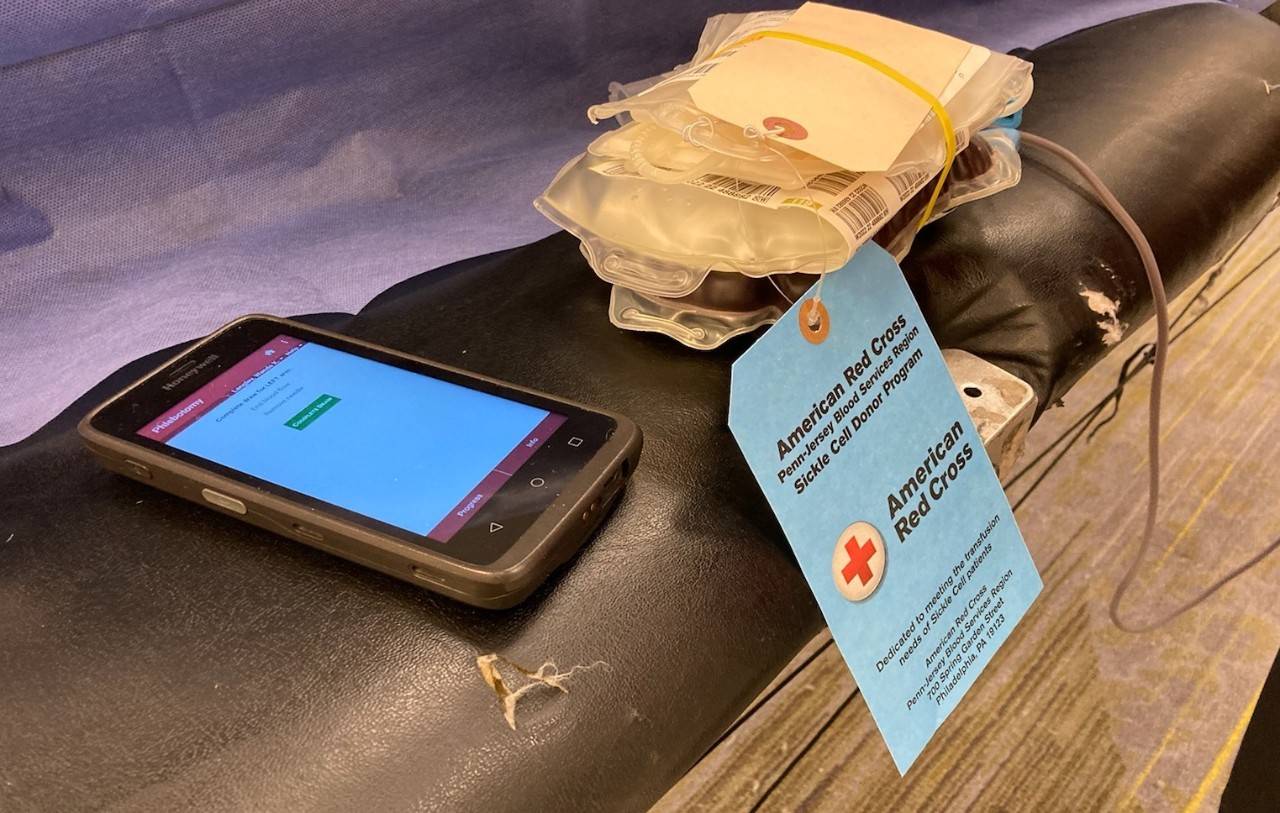

Philadelphia is also home to the Blue Tag Program, a lesser known but critically important first that began as a unique collaboration between the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), the nation’s first pediatric hospital, and the American Red Cross. The program has saved countless lives of individuals living with sickle cell disease by providing blood transfusions that are more closely matched to their own.

Sickle cell disease causes red blood cells to be hard and crescent-shaped – like a sickle – instead of soft and round, making it difficult for blood to flow smoothly and carry oxygen adequately to the rest of the body. Patients can experience complications like severe pain, anemia, infections, stroke and organ damage. It’s the most common inherited blood disorder in the U.S. and primarily impacts individuals who are Black or Latinx. With no universal cure, patients with sickle cell disease rely on lifesaving blood transfusions as their main course of treatment.

Finding the Right Unit of Blood

Repeated blood transfusions over an individual’s lifetime can cause a patient to develop a life-threatening immune response against blood from donors that is not closely matched to their own.

“The difference between the antigens and proteins that sit on the red cells between the donors and the recipients can cause a lot of problems,” explains Dr. Kim Smith-Whitley, a world-renowned hematologist and sickle cell disease thought leader. “One of those problems is antibody formation where your immune system recognizes those proteins as being unlike your own. And those antibodies can make it difficult for you to find the right unit of blood in the future, but it can also cause problems right then and there.”

In fact, getting the wrong type of blood can be even more dangerous than the anemia itself. A patient’s blood count can fall even lower, and in that situation, it’s even more unsafe for them to receive a red cell transfusion.

“It just builds up this vicious cycle, and unfortunately it can get to the point where it’s impossible to find a compatible unit of blood because you have so many antibodies.,” said Dr. Smith-Whitley.

Thinking Outside the Box

While completing her three-year pediatric hematology oncology fellowship training at CHOP in 1992, Dr. Smith-Whitely had a theory.

“If the big antigens are A, B and D that everyone gets screened for, is there a way to screen for the ones that are most discrepant between European Americans and African Americans? And we found those were C, E and K,” she explained.

After finding compelling data and research, she took the theory to one of her mentors, Dr. Catherine Manno, who took it to Sandy Nance, director of immunology and immunotherapy at Penn Jersey Blood Services Region of the American Red Cross. As a result, the Red Cross started screening for C and E in 1995 and added screening for K in 1997.

Introducing the Blue Tag Program

Unfortunately, despite matching programs across the county, antibody reactions were still occurring, largely because not enough African Americans were donating blood. In 1997, the Red Cross and CHOP started an education campaign and began holding blood drives in Black communities. The drives brought in about 50 units of blood per month. After a year, it became obvious more was needed.

“It was raising awareness but not delivering blood in a way that is most beneficial,” Dr. Smith Whitley said. “The blood was available in spurts. You might have an adequate supply one week, and then nothing the next week."

Since blood often has a tie tag on it during processing, the idea for a sickle cell-specific tag was born. By 1999, blue tags were made available at all blood drives – not just sickle cell ones – and were also distributed within Black communities as an educational tool. After being processed, blue-tagged blood from donors who voluntarily identified themselves as Black started being held at CHOP for 21 days, designated specifically for children with sickle cell disease. Blood not used within 21 days was released into the general blood supply.

“We started to bring in 100 to 250 units of blood per month, which was getting better. But we knew at CHOP that we needed about 600 units, and we thought for the general community, we needed about 750 to supply everyone who really needed it,” said Dr. Smith-Whitley.

The missing piece turned out to be a community partner. The Delaware Valley Chapter of the National Sickle Cell Disease Association of America came on board. By 2005, the program was bringing in 1,000 units per month and was expanded to include all Philadelphia hospitals.

“And we did that until the pandemic hit,” said Dr. Smith-Whitely, who by this point was serving as the clinical director of hematology and director of CHOP’s Comprehensive Sickle Cell Center.

Looking Ahead

CHOP continues to lead the way in sickle cell disease research. Dr. Stella Chou, CHOP’s Division of Transfusion Medicine chief, received a grant from the Doris Duke Foundation to genotype match blood transfusions for sickle cell patients, which may further decrease the likelihood of an immune response. Dr. Chou also led the American Society of Hematology’s (ASH) recommendations on blood transfusions, which calls for all individuals with sickle cell disease to be matched for C, E and K at minimum and to get extended matched blood if antibodies are present.

“You can’t choose where individuals get sick,” said Dr. Smith-Whitely. “Sometimes, you would do all this work antigen matching at the hospital where the individual is primarily cared for, but then they would go to college or go on a business trip and get transfused at a hospital that didn’t follow the same rules and come back with antibodies. Patients should be able to have good care wherever they are. I’m really hoping that ASH recommendations will get some traction and that will protect individuals worldwide.”

Drug therapies for sickle cell disease are also available for the first time. Dr. Smith-Whitely was an investigator for the drug Oxbryta® in its experimental stages. Now FDA approved, the medication reduces the need for blood transfusions in some sickle cell patients. In May 2021, Dr. Smith-Whitley was named executive vice president and head of research and development for Global Blood Therapeutics, Inc., a biopharmaceutical company based in California, which she says enables her to broaden her impact. She remains an attending physician in CHOP’s Division of Hematology.