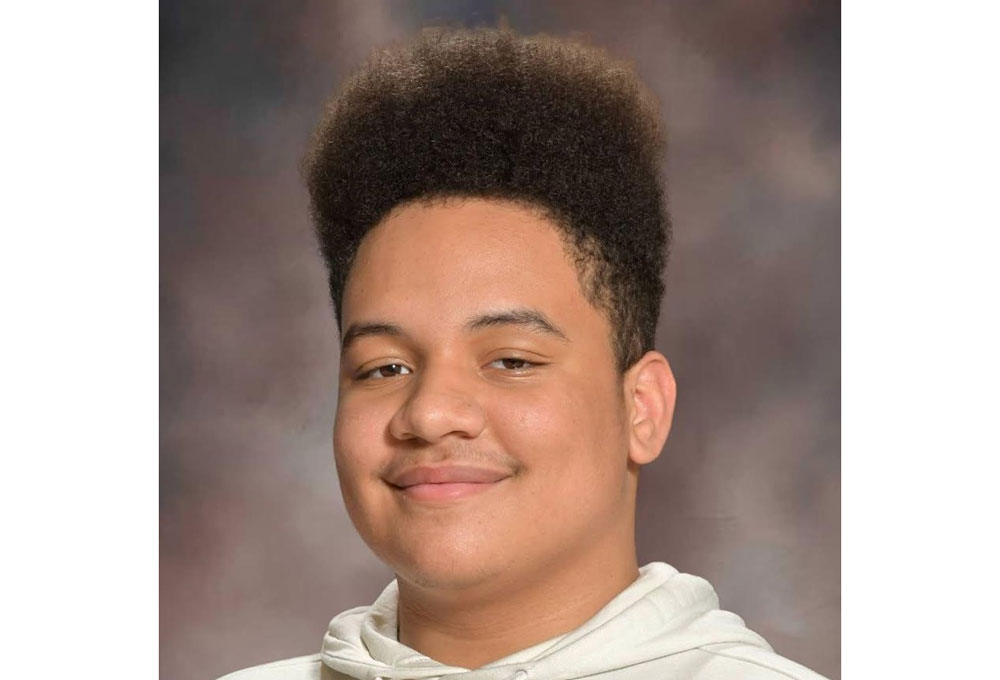

Today, 16-year-old Trayson Harrell is thriving. A junior at Great Falls High, Trayson enjoys gaming and anime, likes to joke around and has also discovered a surprising interest in business.

“He’s taken every business course you can take at Great Falls High,” his mother Amy said.

But behind his quiet demeanor and laid-back personality is a story of survival and resilience.

Just 10 days after Trayson was born, his parents received a phone they never expected. Trayson’s doctor told them their newborn had sickle cell disease.

Sickle cell is the most common inherited blood disorder in the U.S., affecting about 100,000 people. It primarily impacts people of African descent, though it can also affect Hispanic, Middle Eastern and Mediterranean populations. It causes red blood cells to become rigid and sickle-shaped, making it harder for them to carry oxygen. These cells can clog blood vessels, trigger strokes, damage organs and cause excruciating pain. For children like Trayson, even a simple cold could become life-threatening.

In Montana, cases are extremely rare — leaving Trayson’s family feeling isolated and overwhelmed. Trayson’s father Eric is black, but Amy is white, making it extremely unlikely she carried the sickle cell gene.

“I was just like ‘Wait, what’?” Amy said. “Honestly, I had never even looked it up or had even considered it.”

EARLY BATTLES

When Trayson was 1, he was hospitalized with RSV — a respiratory infection made worse by sickle cell. About six months later, following a fun run with his parents, he experienced his first severe pain crisis.

“It hit in the middle of the night,” his mom said. “He was crying and pointing at his arm, yelling ‘bonk, bonk, bonk.’ That was his word for pain.”

A trip to the emergency room followed.

“That was our first pain crisis, and it was horrible,” Amy said.

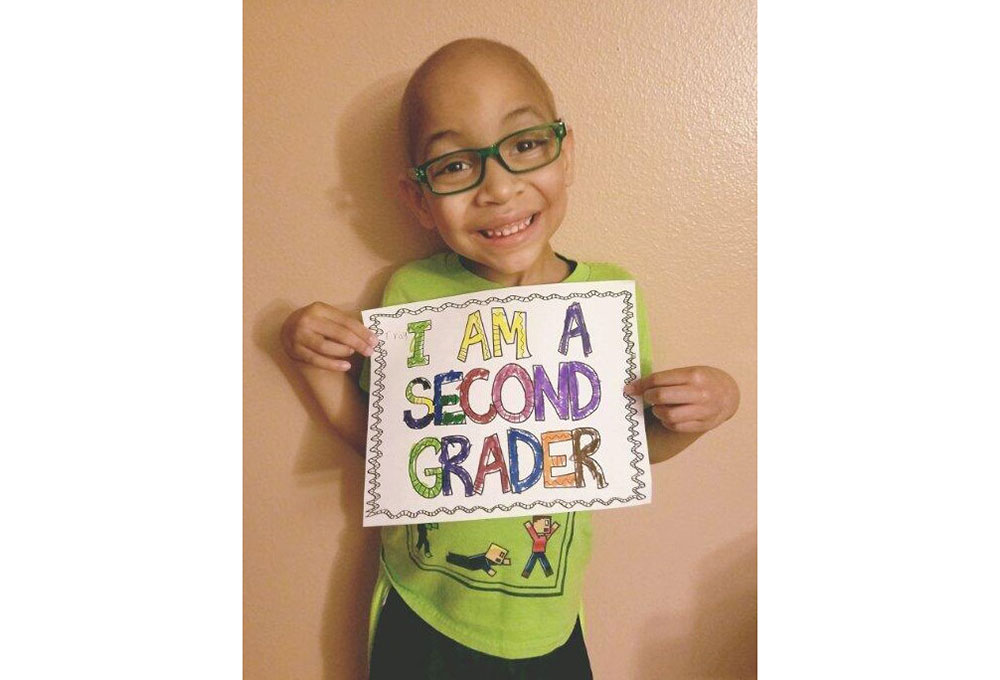

As Trayson grew, the complications multiplied. Pain crises became more frequent and so did the emergency room visits. By age 5, Trayson had been airlifted out of Montana three times for specialized care in Colorado. He endured four episodes of acute chest syndrome — a dangerous complication similar to pneumonia but worse.

“Two of those times he nearly died,” said Amy, a science teacher at East Middle School in Great Falls.

The disease also shaped Trayson’s personality. Years of isolation — avoiding classmates, staying indoors during cold weather and missing school to avoid getting sick — made him cautious and introverted.

“He was kind of an isolation kid, and he never grew out of that,” Amy said.

For Trayson, some of those times are clearer than others.

“I’ve lost more and more memories about it because it’s like my mind involuntarily wanted to move on,” Trayson said. “I primarily remember early on being unable to even go outside and play at school and then being stuck at places for such a long time that they ended up becoming new homes.”

Eventually, the family connected with specialists in Colorado, and a transcranial Doppler test revealed Trayson was at high risk for stroke.

“That was not good news,” Amy said. “I prepared my school for the fact that I don’t know what I’m going to be doing because any day this kid could just have a stroke.”

TURNING POINT

By the time Trayson started kindergarten, doctors warned the Harrells his life expectancy might not reach his 20s without drastic action. His family made the agonizing decision to pursue a bone marrow transplant — the only known cure for sickle cell disease, but also with extreme risk.

“At the time it was only 50 percent survival,” Amy said. “It was like a year in the making by the time I could really fathom signing my name on the transplant paperwork.”

But that was just the start.

Finding a match is difficult, especially for patients of mixed race. But in 2015, the family got the call they needed -- a 24-year-old man matched Trayson on 12 out of 13 genetic markers – better than they could have hoped for

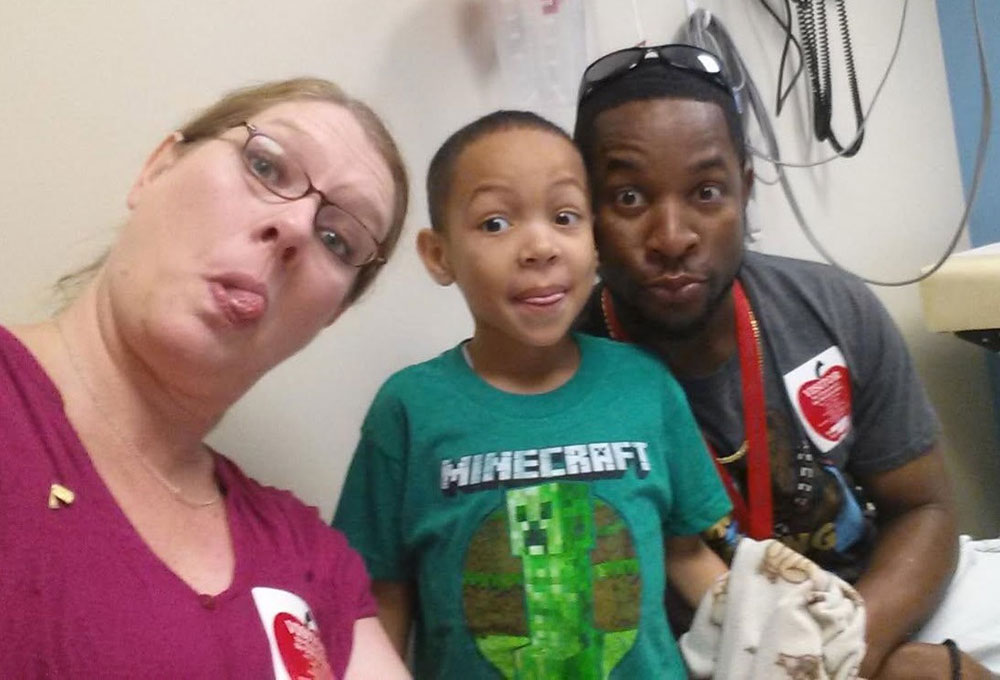

The transplant was grueling. Chemotherapy wiped out Trayson’s immune system, leaving him in isolation. But thanks to his donor — and the blood and platelet transfusions that sustained him along the way— Trayson survived. And the transplant worked.

Trayson’s donor was so moved by the experience that he went to work for a blood bank in Florida, and Trayson eventually got to meet him.

“He was a really sweet guy, and it was amazing to meet him when I was more mature rather than when I was a little guy,” Trayson said. “In my eyes, I would say he’s a part of the family.”

BLOOD DONATIONS MATTER

But it wasn’t just this bone marrow donor who kept Trayson alive. Blood and platelet donors they’ll never meet also played a critical role.

Whenever his oxygen levels dropped or his red blood cells broke down too quickly, transfusions gave Trayson the strength to keep going. Sometimes it was once a month. In the lead-up to his bone marrow transplant, it was every week. During the transplant itself, he received blood almost every other day.

“I would say he had over 30 transfusions in those five years,” Amy said.

Not all blood is the same. Patients with sickle cell often need closely matched blood types to avoid dangerous reactions. That’s why African-American donors are especially critical. Since most patients with sickle cell are of African descent, donors from similar backgrounds are more likely to provide the best match, and the best outcomes.

Trayson is deeply aware of what those anonymous donors gave him.

“Blood donors are definitely amazing people,” he said. “I would love them to know that they are making a difference because they are saving lives like my own.”

LIFE TODAY

Ten years later, Trayson is cured. He still lives with the long-term effects of chemotherapy, but the daily pain and hospital visits are behind him.

Looking back, he recognizes how much his battle shaped his outlook.

“Back then, it granted me a will and determination to pursue being able to be regular and do regular things,” he said. “Today I come to realize there are many things I can achieve as I’ve achieved much harder goals.”

And the family owes a good part of that to those who rolled up their sleeves to donate the blood products that made his lifechanging transplant possible.

“Donating blood is nothing compared to what someone else is going through,” Amy said. “You never know when you might be that lottery ticket for somebody in need.”

BE SOMEONE'S LIFELINE

The American Red Cross works every day to support patients like Trayson. With 100,000 people in the U.S. living with sickle cell disease, the need for blood — especially from African-American donors — is constant.

To make an appointment to donate blood, visit RedCrossBlood.org, download the Red Cross Blood Donor App or call 1-800-RED CROSS (1-800-733-2767).

WHAT IS SICKLE CELL DISEASE?

Support all the urgent humanitarian needs of the American Red Cross.

Find a drive and schedule a blood donation appointment today.

Your time and talent can make a real difference in people’s lives. Discover the role that's right for you and join us today!