By Barbara Gaynes

Last September, while 8 months pregnant with her second child, Erica McKenna began to experience some worrying symptoms.

“I was at home, and it seemed to me that I was having contractions,” she said. “My stomach was so tight.”

She phoned her doctor, and then her husband drove her to nearby Mount Sinai Hospital in Manhattan to get checked out. Within hours she was told that she was in premature labor and would need an emergency C-section.

While that was stressful, it wasn’t the first difficulty of McKenna’s pregnancy. Her unborn daughter — whom she and her husband had named Antoinette — had already received five live-saving blood transfusions in utero, starting at 24 weeks.

“These are really tricky procedures,” McKenna said, explaining that her doctor used ultrasound guidance each time to insert a long needle into her abdomen to reach the umbilical cord — or sometimes the baby’s own abdomen — to transfer the blood.

The transfusions were needed because McKenna had developed a condition called maternal alloimmunization in which a pregnant woman’s blood contains certain antibodies that can cross the placenta and attack the red blood cells of the fetus. This can cause the baby to become dangerously anemic.

“It was really hard going through all this,” McKenna, 32, said of the transfusions, which may have prompted the early labor.

But it was absolutely necessary. Dr. Andrei Rebarber, a maternal fetal medicine specialist who cared for McKenna, said that if the anemia had not been treated, “ultimately fetal death would have occurred.”

In light of a current blood shortage in the U.S. — sparked in part by delayed surgeries due to the pandemic — Rebarber stressed the importance of blood donations as the “easiest way to save a life and make a difference.”

“Our blood-banked blood has a finite shelf life and needs to be constantly replenished,” said Rebarber, who is a Clinical Professor at Mount Sinai’s Ichan School of Medicine and co-director of the Maternal Fetal Medicine Division at Englewood Hospital in New Jersey. “Each year more than 300,000 women and girls die from complications of pregnancy and childbirth worldwide. One of the most common complications from childbirth is hemorrhage. Blood products save mothers and, based on (McKenna’s) case, even babies directly.”

For baby Antoinette — or “Annie” as her parents and 4-year-old brother call her — the medical interventions didn’t end in the delivery room.

“It was a pretty eventful delivery,” Mckenna said. “They had a hard time getting her out. I think Dan, my husband, held her for maybe 3 minutes total and then she had to go straight to the NICU because she was having some trouble breathing. And I wasn’t able to go see her for like 12 hours. It was really rough.”

Annie needed another blood transfusion within 48 hours of birth and ended up staying in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit for 17 days. After going home she received two more transfusions — which were difficult to perform on her tiny veins — before being “discharged” from hematology services in November with a clean bill of health.

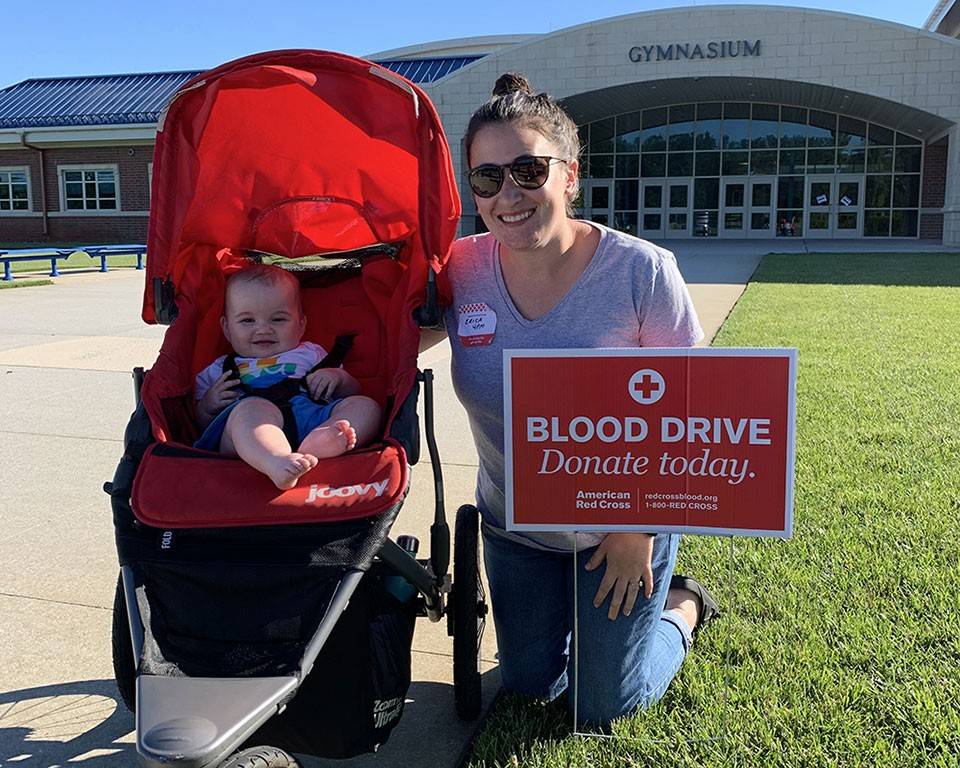

Today, at 9 months, Annie is a thriving baby who has a smile for everyone she meets.

“You would never know she went through all of that,” McKenna said. “She’s happy. She really only cries when she’s hungry or tired.

“We’re extremely lucky. We’re extremely grateful for the people who are donating blood and the amazing doctors who took care of both of us.”

As a way of giving back, McKenna has become a Red Cross volunteer, helping with social media accounts. She and her husband have also started a blood drive through the Red Cross SleevesUp program with a goal of getting 100 people to donate by Annie’s first birthday: September 26.

“Annie’s life was saved eight times,” McKenna said, referring to the eight transfusions her daughter received before and after birth. “She wouldn’t be here without them. To think about her not being a part of our lives now, I can’t imagine that.”