September 11, 2001, marks one of the most devastating days in American history. In the hours following the tragedy, the Red Cross initiated a relief effort that would last years and span the nation, ultimately involving more than 57,000 team members. The majority were volunteers, including thousands who had joined the organization for the first time. These are some of their stories.

Every year on September 11 we reflect on that fateful day in 2001 and on the trying weeks, months and years that followed. We do so to honor those we lost, to comfort those still grieving and to thank those who gave of themselves to help us heal.

Just as our nation was forever changed, so was the Red Cross. Our organization’s relief effort—in New York City, Washington, D.C., and Shanksville, Pa.— was one of the largest in our organization’s history. The response continued for years after the attacks and involved more than 57,000 volunteers and employees from across the country.

No one place was affected as profoundly as our great city and no Red Cross chapter was as deeply impacted than Greater New York; we were at the epicenter of the relief effort. Within moments of the first plane striking the North Tower, teams of Greater Red Cross staff sprang into action to help.

Here is their story:

Minutes after the first plane struck the North Tower, Greater New York Senior Director of Emergency Services Virginia Mewborn and Assistant Director of Operations Max Green left the chapter’s headquarters on Amsterdam Avenue in Manhattan to respond to what they then thought was a small plane hitting the World Trade Center.

Green and Mewborn were planning to evaluate the situation to see how the Red Cross could best support emergency personnel at the scene. On the drive down, Green said he felt that if the building were evacuated early, “…it would have been a long-term canteen operation, where we would support emergency workers.”

As they drove, Virginia paged Red Cross Field Operations Supervisor Luis Avila and asked him to join them. Avila, who was in Queens that morning working a second job, could see the smoke from the North Tower from his location. He told his boss he was leaving, and in fact, never returned to that job. As he left, Avila watched in disbelief as the second plane banked and hit the South Tower.

Mewborn and Green, in their car, began to realize that they had not understood the scope of this incident. “As you got onto the West Side Highway you could see the smoke,” said Green. “My heart fluttered. I looked up at it, saying ‘This, this looks a lot bigger than what I thought it was.’”

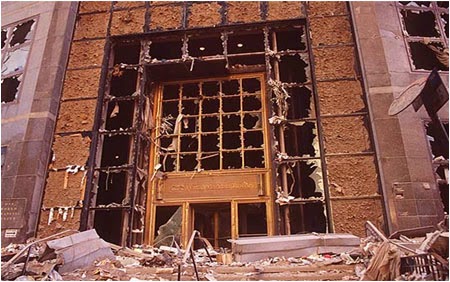

The two parked on West Street, south of Chambers and walked towards the World Financial Center (WFC). They hoped to find a command group—people from partner agencies like the Office of Emergency Management (OEM), who would be coordinating this disaster response with the Red Cross.

Because her cell phone wasn’t working, Mewborn borrowed a phone at a shoe repair store to call headquarters. Greater NY Red Cross CEO Bob Bender told her four things: a second plane had hit, they were dealing with a terrorist attack, Red Cross would set up a Respite Center downtown for survivors and first responders, and he’d sent an Emergency Response Vehicle (ERV) down with a Red Cross disaster responder, Kemagne Theagne, to meet them.

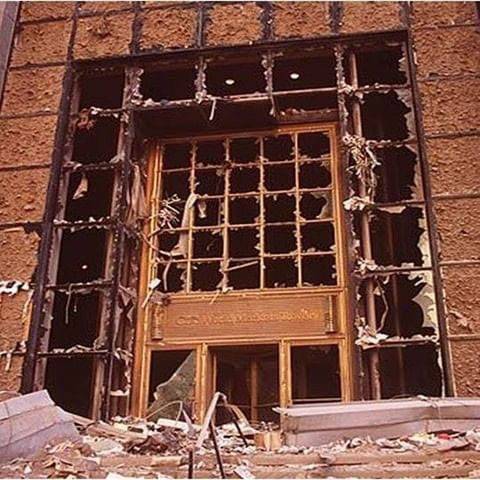

Mewborn and Green found a command post on West Street, right across from the Twin Towers. That’s when they saw a horrific sight—people jumping from the upper stories of the Trade Center. They decided they should not get closer; they should in fact return to the chapter to organize the Red Cross response from there.

Meanwhile, Avila had arrived in lower Manhattan and parked on West and Vesey. “When we get to a scene,” he said, “the first person with a vehicle tries to get as close as they can.” He continued on foot to 7 World Trade, where OEM’s offices were located. “I saw debris everywhere, I was wading through rubble,” he said. As he began to follow a group of fire chiefs, the “haunting scenes” around him convinced Avila he should leave. He turned right to regroup with Green and Mewborn, and the first responders turned left, towards the Towers. Avila later learned they had perished.

As Avila approached the WFC he saw Mewborn and Green, and they walked inside together. “We made a deal that we were going to stay together from that point on,” he said, “that we were going to take care of one another.” Avila was able to contact his wife and let her know he was alright, then the line went dead. “What felt like an earthquake” shook the building. It was the North Tower coming down, but they didn’t know that. They thought the WFC was collapsing on top of them. Suddenly, the building’s windows exploded. Avila grabbed Mewborn and Green. They ran, along with hundreds of others, to the West Side Highway, zigzagging their way back to Green’s car.

Meanwhile, Kemagne Theagne, who had rushed down from chapter headquarters in an ERV, was on Church Street, directly in front of the Towers, trying to find the Red Cross staging area for the relief operation he believed Mewborn, Green and Avila were mounting. He had just gotten out of the ERV to help a woman who had fallen, when he heard, “Pop, pop, pop, pop, pop.” He looked up and saw the North Tower coming down, floor by floor. “I just froze; I couldn't believe this was happening.”

As people ran out of the lobby towards Theagne, a man grabbed him. The two ran together, holding one another, towards a staircase leading into a subway station with a locked gate. They were now engulfed by choking soot and debris. Theagne tried calling his three colleagues, but his Nextel radio was dead. He said to himself, “I hope, I hope, I hope they made it.”

His colleagues were on their way back to HQ. As they drove, they spotted a man in Red Cross gear they thought was Theagne. They stopped and pulled him into the car, only to realize that it was responder Barry Crumbley, who had traveled to the site on his own to find his wife, who worked in one of the Towers. (She made it out safely.)

Theagne spent the next 45 minutes at the foot of the staircase, “just waiting,” trying to breathe, until he saw some light trying to break through the smoke. “We used that little bit of sunlight to guide us out.” They climbed up the stairs and ran.

After washing himself off at a nearby deli along with dozens of others, Theagne made his way back to the ERV. “I said to myself, ‘I got to get this vehicle out of here.’” He slowly made his way out of the site in the dust-covered ERV, “driving through the spider web what was the windshield.” When he finally arrived uptown, covered in dust and ash, no one could believe he had brought the ERV back.

Mewborn, Green and Avila had already returned, also covered in soot from head to toe. “I don't know if [our colleagues] thought we were dead or they were seeing a ghost,” said Avila. “All I remember saying is give me water… I drank about two liters as quick as I could.”

After giving themselves a few moments to wash up and regroup, they remobilized with the rest of the Red Cross team. “After we realized everybody was okay, we needed to make sure that we had supplies down there,” said Avila.

They needed to get the canteen trucks (the ERVs), down to the site as quickly as possible to replenish the water for the survivors, firefighters and other emergency personnel. “Preparations had already begun when we were downtown,” Avila said, “but whatever needed to be finished we continued to do.”

That included creating a plan to send caseworkers to Penn Station, Grand Central Station and the Port Authority, to position ERVs on the West Side Highway and the FDR Drive, and to get ready to set up a relief operation at the Brooklyn Chapter.

“And we knew that help was on the way,” said Mewborn. Red Crossers were coming from upstate New York and National Red Cross headquarters in Washington, D.C. There were also lines of people inside Greater NY Red Cross headquarters, waiting to volunteer, give blood or donate money.

“In those first 12, 24, 36, 48 hours,” Mewborn said, “we registered thousands of volunteers and provided service to thousands of people in New York. We did it well, and we started the platform of how we were going to move forward.”

The heroic actions of the firefighters who rushed into the smoke and flames of the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001 are almost legendary. They gave so much, and 343 paid the ultimate price, giving up their lives to save the lives of others. What few people may know is that five of those who perished were members of the Red Cross Disaster Assistance Response Team, or D.A.R.T., a group of firefighters with Red Cross training who donate their time to help others.

D.A.R.T. was formed as a partnership between the FDNY and the American Red Cross in Greater New York in 1989, when 18 active-duty firefighters responded to an urgent Red Cross call for bilingual volunteers to help 90,000 families in Puerto Rico devastated by Hurricane Hugo. The firefighters were trained by Red Cross and then deployed to Puerto Rico with Red Cross.

Since then, disaster responses have taken members of D.A.R.T. to some of the largest, most devastating natural and human-caused calamities of the last two decades. None hit closer to home than the tragic events of September 11th, 2001.

On that day, D.A.R.T. members numbered 110, most of them active-duty firefighters. Many D.A.R.T. members rushed to lower Manhattan with their respective fire companies, running into the smoke and flames to save lives.

Luis Fragoso, the current chair of the organization, and one of the founding members of D.A.R.T., was assigned to RAC-4 on Roosevelt Island on 9/11, where Special Ops is headquartered. Later that morning, he responded to Ground Zero, where he worked on and off until the end of January.

Fragoso remembers calling into the D.A.R.T phone message line and hearing dozens of messages from retired firefighters who were eager to help with the rescue and recovery operation. (Active firefighters, who were on call at their respective firehouses during this period, were unable to respond with D.A.R.T.)

Fragoso asked two other D.A.R.T. members, Ret. Captain Francis J. Bernard and Ret. Lieutenant Matthew Kiernan, to run the 9/11 D.A.R.T. operation. Bernard and Kiernan stepped up and worked out of the Red Cross Brooklyn chapter, retrieving calls and assigning D.A.R.T. member the tasks of assisting the families.

Many of the more than 120 retired FDNY responders who assisted D.A.R.T. during the 9/11 relief effort eventually joined the group.

Mike Mondello was one of those firefighters.

On 9/11 Mondello was home with his grandchildren in Rockland County, watching TV “in shock.” He immediately packed his gear onto his truck and headed to New York City. Finding the bridges closed, he turned back, ending up at a local dock, where he “hitched” a ride with a man willing to take him and three nurses who also needed transportation to Manhattan on a small private boat. “I can’t tell you what made me go to that dock or where this guy came from, but that’s something I’ll cherish my whole life,” Mondello said.

Mondello checked in with a makeshift command center set up at Ground Zero. “This was still in the opening hours. In the chaos, you picked your own assignment.” He worked at the site for about a week. Then he heard that D.A.R.T. was asking for firefighters to help out at the Red Cross Family Assistance Center at Pier 94 where survivors and family members of those who perished received food, beverages and emotional support. Mondello decided this was something he wanted to assist with.

In the six months that followed, D.A.R.T. alternated between search and recovery at Ground Zero and supporting grief-stricken families of victims. Mondello says of helping the families, "We worked 24/7, taking survivors to doctor’s appointments, shopping, wherever they had to go.”

He said it was especially meaningful for D.A.R.T. members to be helping the families of fallen firefighters. “We had a deep personal connection with them and they with us. There was a level of comfort in that they felt that a brother was taking care of a brother.” In fact, Mondello called supporting the families “a life-changing experience.”

Most, if not all, D.A.R.T. members feel the same about their D.A.R.T. service. “Without being involved with DART there would be a void in my life,” said Robert Reeg, a WTC responder who joined D.A.R.T. in 2006. “It gives you a feeling of fulfillment, and I think everybody needs a bit of that.”

Although Reeg was seriously injured on 9/11 by falling debris, he was fortunate to live to tell about his experience. Sadly, one of the five D.A.R.T. members who died was a good friend of Reeg’s, “an all-around warm, caring guy to work with and a committed firefighter.”

“It was very tough to lose those guys,” said Fragoso. “They were dedicated to D.A.R.T., dedicated to the Red Cross and dedicated to the people of New York.”

Although Mondello didn’t know the five who were lost on 9/11, he said, “They were still my brothers.”

Reeg added that the D.A.R.T members and other firefighters who lost their lives during 9/11, "died doing something they loved. We’re a brotherhood and a sisterhood and we like to give back to the community. We honor their memory by continuing to serve."

Through D.A.R.T. they are able to do just that.

The Greater New York Red Cross pays its deepest respects to the five D.A.R.T. members who lost their lives on 9/11 and to their families: LT. David J. Fontana; SQ-1, FM. Vincent D. Kane, Engine-22; LT. Thomas R. Kelly, Ladder-105; FF. Gregory Saucedo, Ladder-5; and FF. Gerard Schrang, Rescue-3.

LT. David J. Fontana

SQ - 1

FM. Vincent D. Kane

Engine - 22

LT. Thomas R. Kelly

Ladder - 105

FF. Gregory Saucedo

Ladder - 5

FF. Gerard Schrang

Rescue - 3

September 11, 2001, marks one of the most devastating days in American history. Over twenty years later, many can still recall their own 9/11 experiences as if they’d happened yesterday.

Through their grief, Americans came together in unprecedented ways to respond to the unimaginable events. Many offered their time and compassion to others while struggling to cope with the tragedy themselves. Some were inspired to become Red Cross volunteers, helping the country cope and heal by working at the front lines of the organization’s massive relief effort, or simply supporting their own neighbors.

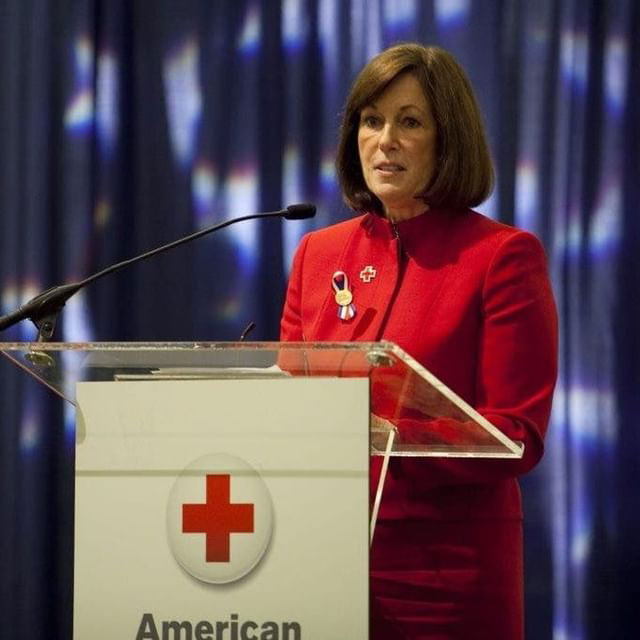

"We owe so much to all who gave of themselves to help our city and our nation heal,” Mary Barney, CEO of the American Red Cross in Greater New York, said. “Two decades later, we continue to honor the heaviness that this day carries, and we offer our compassion to every American still grieving.”

In the hours following the tragedy, the Red Cross initiated a relief effort that would last years and span the nation, ultimately involving more than 57,000 team members. The majority were volunteers, including thousands who had joined the organization for the first time.

Over twenty years later, many are still active team members who regard 9/11 as the inspiration for their long and continuing Red Cross journey. Each holds memories of that day that are tinged with moments of both grief and hope.

These are some of their stories:

SAL MONTORO

Like many New Yorkers, Sal Montoro vividly remembers the events of 9/11. From his workplace in Long Island City, he watched smoke fill the blue sky from across the East River.

Within hours, Montoro and staffers from the lumber company where he worked had mobilized to haul building materials to the site of the fallen towers to support the recovery effort. He recalls slicing open his hand while operating a forklift. As fate would have it, he was treated by members of a Red Cross relief team stationed in the Financial District.

“I promised that when I had the time, and when all the crisis started to slow down, I would look into joining the Red Cross,” Montoro said. “I ended up joining in January.”

Nearly 20 years and thousands of volunteer hours later, Montoro remains a dedicated member of the team, serving as Mass Care Chief and Disaster Action Team member.

An additional inspiration for Montoro was the death of a friend who had been in one of the towers.

“I always keep his picture with me in my Red Cross bag,” Montoro said. “It reminds me why I’m doing this.”

Montoro has since taken part in relief and recovery efforts following both local and national disasters, as well as encouraged his son and daughter to become volunteers. He credits 9/11 as a turning moment for him in his relation to volunteer service and community aid.

"You couldn’t just be yourself anymore. You couldn’t just be one person; you couldn’t just be you and your family. You had to think larger... because if something like this happened again, the only way to stop it is for all of us to be combined as one,” Montoro said. “The Red Cross was the perfect place for me. I thought it was a perfect fit for what my mentality was.”

Looking back on the events of 9/11, Montoro said that visiting New York’s Financial District still evokes dark memories for him. In his mind, he hears the sirens that blared to notify volunteers that surrounding buildings were about to collapse and they needed to flee the area. He also recalls the moments of silence that followed the discovery of bodies amid the rubble.

“I think that we should just never forget.”

CARMELA GRANDE

Carmela Grande, a longtime nurse, was out of the country in New Zealand at a work conference as events unfolded on 9/11. She recalls the people around her being so supportive and comforting, knowing she was a native New Yorker.

Upon her return, she immediately sought out the Red Cross to engage in the recovery efforts, initially by making beds at a relief center for exhausted first responders and other volunteers working around the clock near Ground Zero.

“I did anything they wanted me to do,” Grande said. “I made more beds than I made in my whole nursing career.”

She also supported families whose loved ones had been killed in the attacks or were still missing. One moment stands out to her from that time: assisting a pregnant mother who had lost her husband in the tragedy.

“There were many families like that,” Grande said, her voice breaking. “You didn’t even have to talk. Just hold their hand.”

Grande admits that she did not think she would stay with the Red Cross for 20 years. It was the people — fellow volunteers and those in need of assistance after emergencies — who have kept her engaged, she says.

Since 9/11, Grande has provided health support to those impacted by countless emergencies in NYC and across the country.

“We’re here to help them in crisis,” she said. “That’s the part of it that keeps you going: to help others.”

RICHARD SANFORD

Richard Sanford was a high school teacher in Brooklyn when the tragedy occurred. He remembers seeing the smoke from the collapsing towers and immediately understanding the severity of the situation. He also knew that he needed to inform his students about what had happened.

“I saw one boy was very nervous,” Sanford said, “Very shaken up. I said to him, ‘Are you OK?’ He said, ‘My mother works in that building.’”

He then learned that the child’s mother had not yet left for work that day. “I remember saying to him, ‘She may not have a job tomorrow, but you got your mother.’”

Having fond memories of supporting the Red Cross as a child, Sanford was immediately prompted to join the organization's relief efforts.

“My job was to shuttle people from the Brooklyn headquarters to the 9/11 site — what they call the Ground Zero site,” Sanford said.

This was the ideal job for the native New Yorker who, in addition to being a teacher, also worked as a tour guide. Sanford recalled spending months giving mini tours to the volunteers, pointing out the city's different landmarks as he shuttled them across the area.

“I felt that that was also an obligation of mine, to let people know where they are — give them a little perspective about New York City and a little joy about New York City.”

Sanford recalls the gratitude that people had for the Red Cross, particularly following the events of Sept. 11.

“Any time we did something, and they saw that Red Cross van,” Sanford said, “people just opened up to us.”

He also remembers the sorrow that came in the aftermath and the way the New York atmosphere changed.

“It was a very sad time; it was a difficult time. We couldn’t wait for the city to come back to life,” Sanford said. “The smell of the building burning just stayed with you, and it probably still stays with me today.”

Following the 9/11 recovery effort, Sanford knew he would remain with the Red Cross. He now serves as a Red Cross preparedness trainer and teaches volunteers how to drive Emergency Response Vehicles. Recently, he supported relief efforts for victims of California wildfires.

The ability to aid people after disasters and crises, and the ability to make a change in their lives, is what makes his work with the organization meaningful to him.

“I never felt that I would leave the Red Cross, since 9/11. I felt at home. You know, as a kid I was with the Red Cross as a volunteer, and as a teenager, and then I came back home again after 9/11. So it was very meaningful to me.”

GEORGINE GORRA

Georgine Gorra, a native New Yorker with longstanding roots in downtown Manhattan, watched the first plane hit the Twin Towers from her living room in Brooklyn. She had a gut feeling that the turmoil was only going to get worse.

“I called everyone I knew who was down in that area, including people in the World Trade Center themselves. I said: ‘You get out,’” Gorra said.

Luckily, everyone she knew made it out of the area unharmed.

A social worker and professor, Gorra had experience teaching courses on death and resiliency; her expertise in these fields would be crucial to recovery efforts. Within hours of the tragedy, Gorra had already contacted the Red Cross and walked to the organization’s Brooklyn office to begin her volunteer work helping to calm those struggling with the unfolding events.

“They asked me if I was going to leave New York,” Gorra said of a group of frightened tourists she encountered a few hours after the attacks. “I said ‘Absolutely not.’”

Many times, Gorra’s job was simply to listen to what those affected had to say and comfort them as best she could. But like the individuals she was helping, Gorra’s perspective on life was changing.

“I take every day with a sense of deliberate wanting to accomplish something, and being grateful always, with a sense of gratitude that I was able to — even though I was affected by it — I was able to grow from it,” Gorra said.

While she acknowledged the pain it brought, she also respected the way 9/11 changed her worldview.

“How do you know how something like that is going to transform you?” she asked. “But it will transform you if you let it.”

Like many Red Cross members, Gorra did not expect to volunteer for 20 years. She credits the fulfilling work she has done through the organization with keeping her on board.

“[Red Cross team members] were finding things within the Red Cross — and there were so many things to do that I would fit into, that I would be good at and enjoy,” Gorra said. “That’s why I stayed.”

Since joining, Gorra has volunteered with nearly every department in the organization, including Disaster Cycle Services, Service to the Armed Forces, and International Services. Reflecting on her time with the Red Cross, Gorra said that all her experiences have given her an overarching sense of belonging — as well as a community of people all “cut from the same cloth.”

“I think what the Red Cross has brought to me is a greater understanding of what it is to be a humanitarian, what it is to be a human being, and what it is to truly love one another,” Gorra said. “It’s a great example of how to build community.”

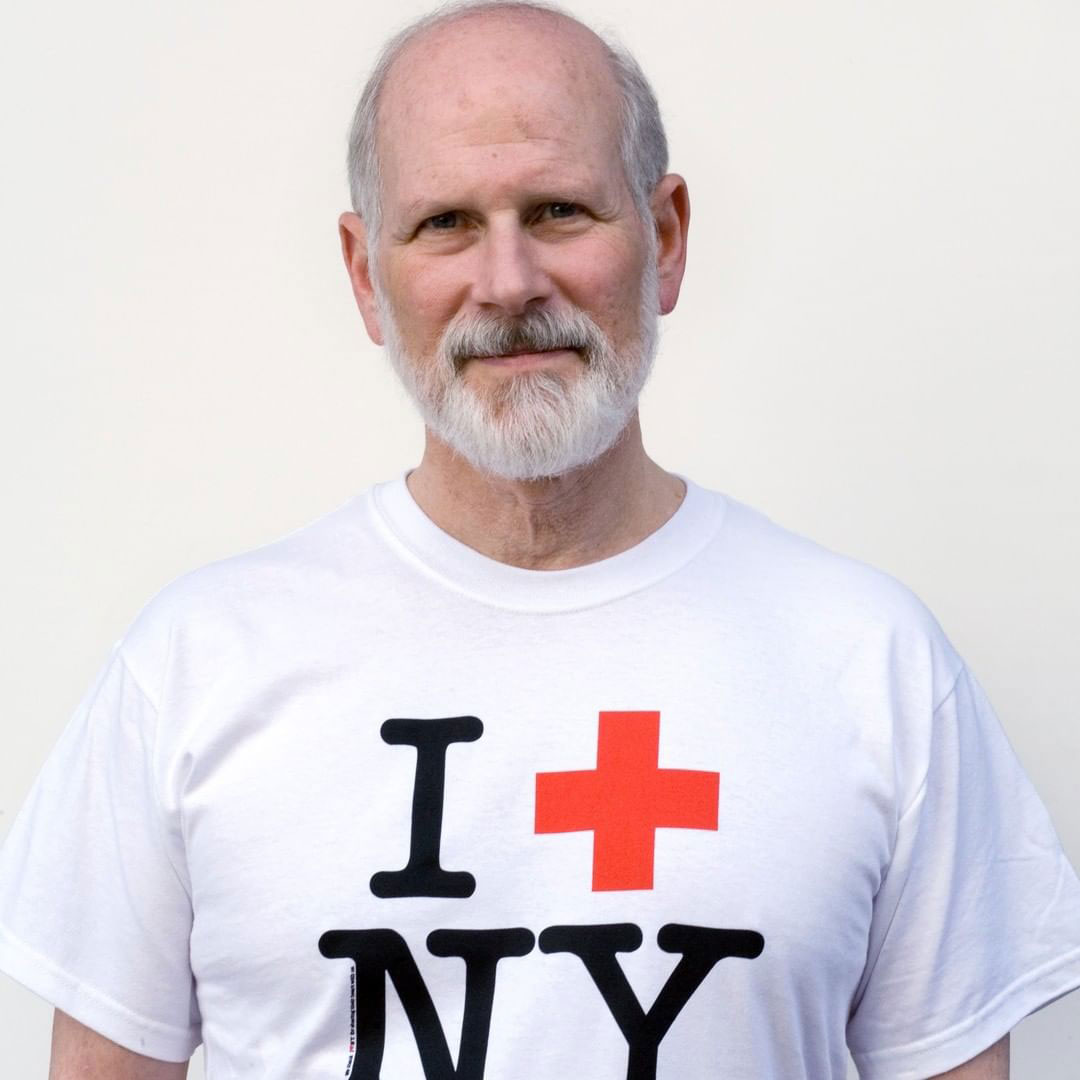

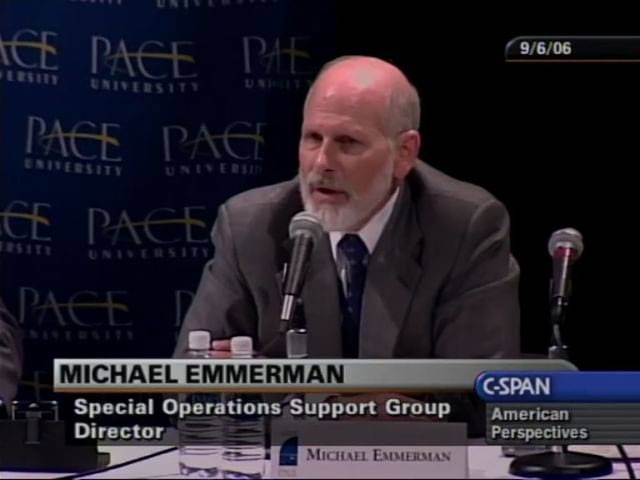

MIKE EMMERMAN

1 of 3

2 of 3

3 of 3

My most vivid memories are the ones that are ingrained in my head relative to the towers falling and being trapped under the south tower for several hours.

I was responding that morning because I saw the first plane hit from a doctor's window and made my way down to Ground Zero. Before it was Ground Zero, it was just an airplane hitting a building. When the second plane hit, we all pretty much knew that it was an attack. I had been responding to try to get to 7 World Trade Center where the New York City Emergency Operations Center was at that time. As it turned out, they had been evacuating 7 World Trade and setting up the command centers on West Street and Church Street. I ended up on the Church Street side with fire, police and EMS. I was representing Red Cross at that command post.

I vividly remember that three chiefs from NYPD who knew me, Chief Esposito, Dunne, and Allee, came by. Chief Allee asked if I would set up a temporary morgue, thinking we needed one, and I agreed to do that. Then the three Chiefs got into a car. I did not know for a long time where they went but they left. I had to finish some organizational items at the command post. As I finished those things and started to walk away from the command post, in order to go up Church Street to one of the churches to try to set up a temporary morgue, the South Tower fell.

It was a matter of a difference of 10 or 12 seconds that we are having this conversation, because everybody I had been standing with got killed. I was lucky, I got trapped by the debris but survived. So, those sights, sounds and smells stick with me and will be with me forever.

Twenty years later on 9/11, I'm having a gathering at my home of seven of us who were there that morning. We have done that pretty religiously for the major anniversaries. I know that we don't even have to talk about what happened that morning, it just lives within us. I operate life normally, I am fine, and I continue to work with Red Cross and respond. I am the Emergency Management Regional Program lead for the Greater New York Red Cross, and all of us just continue responding when needed. The 9/11 experience just comes up in a flood of images and memories on the anniversaries, especially this one being the 20th.

I believe that life, for me and for others, has moved on and we continue to serve. Some of the people I served with that morning are now at NTSB, FBI, FEMA, or other entities that respond to human needs. Almost all of us are continuing to do things that serve the response community. I've been with the organization for over four decades because I believe in the mission. I have lived through eight different iterations of management at the ARC, and have seen changes of protocols, and other things, but the mission stays the same. So for me, it is that service to the community, for people who are devastated by disasters that I keep doing this. It's just part of my being.

It was because of Chief Allee that I am able speak about my experiences on 9/11 today. Chief Allee passed away in 2018 due to a Ground Zero related illness.

ANDREA GRIMALDI-GRAFER

1 of 3

2 of 3

3 of 3

I had just turned 26 years old. The Red Cross was my life at that time. I was young, energetic, and enthusiastic about my career and what opportunities were available to me in the organization. I managed our youth programs and worked in close cooperation with our blood services program, doing community outreach and helping set up and run blood drives.

I was driving to a meeting in Yonkers, listening to the traffic report, which I did because I lived in Northern Westchester. When I got to the site of the meeting, the TVs were on and everyone was in a panic. The first plane had hit and I immediately called the office. I could hear chaos in the background. I jumped in my car and ran right back to the office in White Plains, about 15 miles from where I was.

When I got there, they were readying our Emergency Response Vehicle to go down to the site, not knowing what really was happening, but knowing there were people in need. I remember being scared because my fiancé at that time was one of the volunteers in the ERV. Everything just happened so fast. It unfolded in such a way that was almost surreal. You're watching and listening to what's going on and trying to understand what just happened.

As our team rolled out and made contact with us, the second plane had hit. They parked and waited to see what to do next. The operation started unfolding from there.

We had former President Bill Clinton come and visit us because he was living in Westchester County at the time. He had called the Westchester County Executive to say, ‘Where can I go? Where can I go to help or do something?’ The first place the County Executive at that time said is go to the Red Cross.

We stayed at the chapter house for several days after it happened. We were beyond 24/7 operation. At three o'clock the next morning, I'm sitting in our front lobby and we had lines of people standing outside our door trying to sign up to volunteer. I remember walking outside and saying to them ‘Thank you so much. I'm going to get your contact information. We're getting things together, but please go home and rest and then come back.’ And people were like, ‘But we can't. We want to do something. We want to help.’ It struck me at that time how important the Red Cross is as that place of hope and help that people came to. And in their restlessness, they came to us and not just for us to help them feel less restless, but for them to do something and to be able to give and to be able to help and make the situation better.

We cleared out our parking lot so that we could have pallets of water dropped there, because we became a central distribution center for getting supplies down to New York City. I think I processed well over a thousand and deployed over 800 volunteers, and that was training and working. Those volunteers came back from Ground Zero with things they've never seen in their life, but they kept going back. They didn't say, ‘I can never do this again.’ It was ‘Send me back.’ It was amazing. It was such a Herculean effort that was unlike any other. There are no words to describe it. It stays with you. Some days it seems like it was yesterday and some days it seems like it was more than 20 years ago. It was and continues to be such a point of pride for me to be able to say that I was a part of that. I was a part of a historical response, that I was able to do something in a situation that made so many feel so hopeless.

After 9/11, I started to identify myself as a Red Crosser. It wasn't that I worked for the Red Cross. I was a Red Crosser, as I knew that I was in it for the long haul. It made an impact on me as a person and solidified that my goal in life was to want to make a difference and be part of making things better in a bad situation. People know that when something like this happens, the Red Cross is a part of the help. We're a part of the recovery, the hope, and making a horrific situation, in some way, better for those people who are affected.

PAMELA FARR

1 of 3

2 of 3

3 of 3

On 9/11, I was Board Chair of the Red Cross of Greenwich chapter. As a member of the Red Cross, you were just doing things that day that felt like the right thing to do for the community on that horrific day. Everyone was personally a little distraught because everyone knew someone who might have been there.

One of my sons worked in 7 World Trade Center, the building that collapsed the evening of 9/11 from damage sustained when the towers fell. Although we had heard that the buildings around the two towers had been evacuated, we were still seeing horrific ‘live’ footage of those evacuated fleeing the area as the two towers collapsed. My son was among them. Cellphones weren’t common yet and many communication networks were down or overloaded. It would be 2 days before we knew he was safe.

So, there was a personal side and panic to everyone's emotional response. But everyone also put on their Red Cross hat and knew that our responsibility was to do whatever we could for our community. Everyone pitched in and helped. My whole board came in, all of our disaster volunteers came in, all of our youth volunteers came in. There was this personal, ‘Oh my God, what's going on.’ And, ‘I can't find Aunt Suzie.’ To, ‘Okay fine, what do we have to do right now and what do we have to set up to do tomorrow?’ All of us kind of put our own concerns aside and were trying to do what we could for the community.

We knew that the city was completely shut down, communication was almost impossible and there would be parents who might be unable to reach their children and pick them up from school. The Greenwich chapter staff and volunteers set up a shelter for those children where they would be cared for and comforted. A Red Cross shelter for ‘children only’ was unprecedented, but on that day we knew it was needed.

Sometimes you have to be creative in that sense. In fact, that's what leadership is about, isn't it? Making decisions that need to be made on the spot, based on experience and need.

That evening, all the houses of worship in Greenwich coordinated a gathering of their congregations to provide comfort and spiritual support. Members of the Red Cross board fanned out to those services across town to let the community know that the Red Cross was prepared and ready to meet any needs they might have, be it helping locate family members, mental health support or giving blood.

Over the next days and weeks, Greenwich first responders were being asked to help at the Trade Center site, and of course they went without hesitation. Those local brave men and women would do their shifts at ‘the pile’ and then many would come by the Greenwich Red Cross to decompress before going home to their families.

The one ray of hope and goodness I saw during those challenging times was the outpouring of compassion, caring and empathy on the part of the Greenwich community. The community rallied in support of the Red Cross and everything it does. We couldn't do the things we needed to do after 9/11 because our chapter house wasn’t large enough—the community helped us purchase the building that the chapter is now in. Many spaces in that new building were named in honor of our neighbors lost on 9/11.

SIDNEY KO

1 of 3

2 of 3

3 of 3

I actually started as a youth volunteer in 1995. In 2000, I became a customer service assistant at the Queens office. My job was to take care of the day-to-day operations at the Queens area office.

When you're a 20-year-old, you're just thinking it’s a job that didn't pay well. But once 9/11 happened, my peripheral just opened up, like a total 360. It was one of those a-ha moments where I finally figured out this is what the Red Cross does and it's amazing how they do it. We are the soldiers of humanity.

This was my first taste of getting into this type of disaster operations, transitioning from community outreach to disaster operations.

Shea Stadium, which is now Citi Field, became a respite center for 9/11 rescue workers that were coming in from all over the country. The Mets organization allowed us to bring in cots and blankets and create a rehab area where people could take a shower, rest up, and then be bused back to Ground Zero. Our volunteers, including myself went to Shea Stadium to assist with the operations over there.

When you see the work we do, whether it be physical, such as providing sheltering and staffing a respite center to even mental health. Mental health was not something I even thought of as a young person, but after 9/11, I realized the mental health aspect of things, of how it can affect an individual, including myself.

We worked with really great disaster mental health workers, and they really opened my eyes because of the young volunteers we had. A lot of our volunteers came from Stuyvesant High School, which was in the impact zone of 9/11. Most of them saw things they probably shouldn’t have seen at the World Trade Center. As they evacuated the building, the towers had already crumbled and as they were running, the dust was just chasing them. That type of traumatic experience, when you're dealing with 14- to 18-year-olds, some of them were sleepless. There was sadness, but there was also a lot of hate. We had one individual of the Muslim faith and he was afraid of going out in public.

Mental Health came and said this is something we have to deal with. This is a great opportunity to get all the youngsters in and we had several sessions of like 25 to 30 people. We had an open discussion about what happened and how does everyone feel. It was a good session for them to decompress and when you saw the eyes of those individuals, we changed the lives of those youngsters. I think if we didn't intervene then, their negativity would probably have impacted their lives today.

After doing my time at the Queens chapter, I went over to Disaster Services in staffing. I went into logistics and field communications, and the communication part was really my thing. I was really into radio operations. Technology was something I really wanted to get into. My logistics and field communications experience is the reason why I was hired over at New York City OEM.

9/11 opened an opportunity for me to understand the emergency response aspect of it. And that is why I'm pretty much here now at this agency. I’m now the program manager of our emergency support center here in New York City. It was an evolution in my career.

MAX GREEN

1 of 6

2 of 6

3 of 6

4 of 6

5 of 6

6 of 6

My mother was a volunteer; she worked for FEMA on a temporary basis. When there was a major disaster anywhere in the United States, she was called upon to respond. She came back after some major responses and told me incredible stories about her experience and the people that she worked with and how rewarding it was for her.

After she passed away, I went to my local American Red Cross chapter in Queens, and I interviewed as a Disaster Services volunteer. And one night on duty turned into two nights on duty, to three nights on duty a week. I was eagerly learning more about the field, responding to disasters, helping people in their time of need, the amazing volunteers that I worked with, it was all new and exciting to me. I became a team captain. I was hooked immediately.

On the day of 9/11, we received reports about the first plane crashing into the first tower and I ended up driving down to the World Trade Center site with the director of the Disaster Services at that time, Virginia Mewborn, and one of my colleagues, Luis Avila, met us down there. We were talking with the New York City Office of Emergency Management, the fire department, and other responding agencies, but we weren’t there gawking and looking at what was happening. Certainly, we had an awareness of what was going on around us, but we were mission focused. It was us trying to figure out, how was the Greater New York chapter going to be a part of the response? How are we going to help the victims? How are we going to help the family members of the victims?

And that's what led us into the Winter Garden at the World Financial Center that morning, looking for a room where we could set up a family assistance center. And we happened to be in the Winter Garden when the first tower came down. We ran outside of that building back towards the water. Being focused on our mission that morning actually saved our lives. That's what I've come to realize. So not allowing yourself to stray too far out of your lane and start doing things that aren't within your immediate mission are really crucial to the success of your operation and your response.

I remember coming back from the towers, the destruction downtown, and you could barely walk across the plaza at the Greater New York chapter, because there were that many people that were waiting online to find out how could they help, where could they make a donation, where could they donate blood, how could they sign up to be volunteers. For the days, weeks, months following the events of that day, people came together. We were one Red Cross in the true meaning of the word that day.

That was the largest response that we had ever been a part of, but we had our day-to-day operation that needed to continue. There were still residential fires, and other incidents that were happening the day of 9/11. There were a number of people that were assigned to the immediate response to the events of 9/11, and the rest of us remained focus on our day-to-day mission.

I wanted to work in the 9/11 operation. To say I wasn't a little disappointed would be a lie. But at that moment, I also understood that our day-to-day work was as important. The Greater New York chapter was one of the busiest chapters from a day-to-day perspective in the country. And that didn't change following the events of 9/11. So, I took my assignment. I knew what my mission was, and I was proud to be able to support the chapter along with my colleagues on the days after.

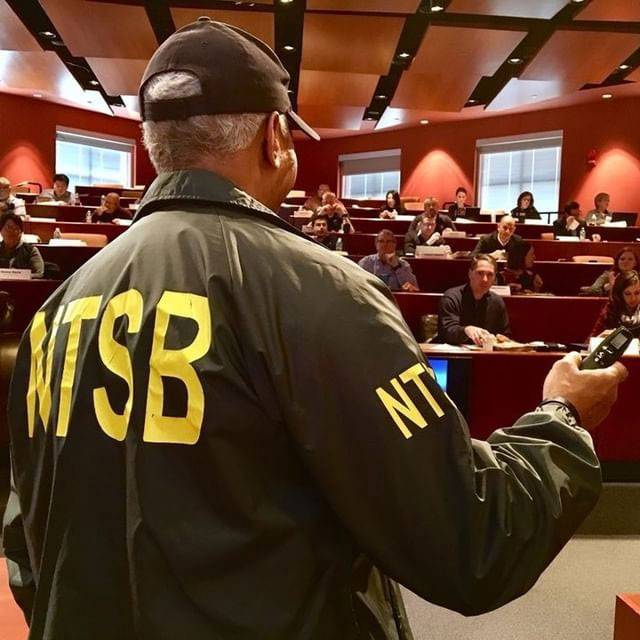

Right now, I'm the emergency operations coordinator for the National Transportation Safety Board. We respond to transportation disasters across the country. We work with local state and federal agencies in their planning and training for a family assistance operation in the aftermath of a mass casualty incident.

One of the things that I love about this position is that the NTSB has a partnership with the American Red Cross National headquarters. I still work very closely with the American Red Cross. It's a great feeling to go onsite of a major transportation accident and see Red Crossers out there and be able to introduce myself as a former Red Crosser, and still do amazing work with them.

I think what really prepared me for this position, gave me the experience, the training, and just the resume to be chosen, is the 10 years that I spent in emergency management or disaster services in New York, working at the American Red Cross with an incredible group of people. I don't know if there's anywhere else in the country that you can get the same level of experience. Everything from residential fires to manhole explosions, water main breaks, you name it, it happens in New York City, and the American Red Cross, and our mission is to help people in need.